Dear all, this is the final entry to my coverage of April’s MAGS compo. For more information on the competition and the previously discussed entries, you should take a look at the first and second part of the article. This Sunday instalment takes a look at the remaining three contestants: Hard Space, Snakes of Avalon and Space Pool Alpha.

Dear all, this is the final entry to my coverage of April’s MAGS compo. For more information on the competition and the previously discussed entries, you should take a look at the first and second part of the article. This Sunday instalment takes a look at the remaining three contestants: Hard Space, Snakes of Avalon and Space Pool Alpha.

Once more, don’t forget to cast your vote! The compo is still ongoing and lasts until the 17th of May.

Hard Space

Our first entry today, Hard Space: Conquest of the Gayliks, continues on the path already taken by Shane “ProgZmax” Steven’s previous game, Limey Lizard: Waste Wizard!, only to bring the parodic aspects even more to the fore. Stevens is also responsible for the vastly, vastly different Mind’s Eye, one of my all-time favourite AGS games.

I do absolutely have to get this out of the way: Hard Space is a parody of the original Star Trek, built entirely on the solid foundation of cock-jokery. The game, set on the ISC (or is it I.S.S.?) Penetrator, “a ship crewed almost entirely by male homosexuals,”1 discusses the all-star entourage of Captain Jack Hardin, “the black sheep of the Interstellar Commonwealth.”1

I do absolutely have to get this out of the way: Hard Space is a parody of the original Star Trek, built entirely on the solid foundation of cock-jokery. The game, set on the ISC (or is it I.S.S.?) Penetrator, “a ship crewed almost entirely by male homosexuals,”1 discusses the all-star entourage of Captain Jack Hardin, “the black sheep of the Interstellar Commonwealth.”1

Admittedly, the foundations for a game like this do exist; not only do we have the legacy of Interplay’s Trek point and click adventures 25th Anniversary and Judgment Rites, but also this (never in my wildest dreams did I think I would be linking it here):

Also aboard the starship are the Vulvan Cmdr. Spunk and Lieutenants “Scatty” Scatman and Tagai. I’m sure you get the gist. The captain, visibly shaken by the loss of the only female crew member on the ship to a tragic accident, bounces into a pair of levitating on-screen boobs that divert the ship’s course over to Fallux V in the Boner System.

First things first: Our good Cpt. Hardin has a permanent, raging hard-on (see screenshot on the right). Now that we have that out of mind (but not out of sight, especially now that I just subjected you to a screenshot, sigh), what we have here is an extremely full-fledged one-month project, a whole package. Intro? Check. Unique visual style? Check. Animations? Check. Inventory? Check. Gadgets? Check. A music volume slider?

First things first: Our good Cpt. Hardin has a permanent, raging hard-on (see screenshot on the right). Now that we have that out of mind (but not out of sight, especially now that I just subjected you to a screenshot, sigh), what we have here is an extremely full-fledged one-month project, a whole package. Intro? Check. Unique visual style? Check. Animations? Check. Inventory? Check. Gadgets? Check. A music volume slider?

Chekov! In fact, the game is so full (of itself) that it simply has no regard to the compo’s rule set: not only is the game made by three people (in addition to Stevens, Jim Reed contributed backgrounds and ShiverMeSideways music), but it also blatantly breaks the one-room rule! The nerve!

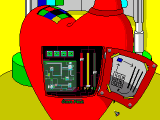

Some issues with the game’s interface are inherited from the aforementioned Limey Lizard: I would have absolutely preferred a revolving cursor - especially since only three actions plus look at exist - instead of having the buttons sandwiched in a cluttered, super-duper-miniature interface. Additionally, for sci-fi tech, Hardin’s WristCom (on the left) is positively retro-grade: For scrolling text, the communicator has buttons for left and right instead of the more semantic and logical up and down. Also, while its database access works by inputting searches on the keyboard, you still have to switch back to using the mouse to actually enter one. There’s always the chance, though, that Stevens is a fan of Tale of Tales, and these gaffes in the interface have been included to illustrate the incompetence of the Interstellar Commonwealth…

Some issues with the game’s interface are inherited from the aforementioned Limey Lizard: I would have absolutely preferred a revolving cursor - especially since only three actions plus look at exist - instead of having the buttons sandwiched in a cluttered, super-duper-miniature interface. Additionally, for sci-fi tech, Hardin’s WristCom (on the left) is positively retro-grade: For scrolling text, the communicator has buttons for left and right instead of the more semantic and logical up and down. Also, while its database access works by inputting searches on the keyboard, you still have to switch back to using the mouse to actually enter one. There’s always the chance, though, that Stevens is a fan of Tale of Tales, and these gaffes in the interface have been included to illustrate the incompetence of the Interstellar Commonwealth…

To the game, then: The first puzzle proper, fixing the “Transputter,” (on the right) is unsolvable to me. Now, I don’t know whether I’m confused by the letters X, Y and Z normally being used for denoting axes in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, or whether I’m too much of a humanist to understand how the circuit board is supposed to work here, but with zero feedback from the game and several hours of cracking open the puzzle for the sake of a democratic write-up, no can do!

To the game, then: The first puzzle proper, fixing the “Transputter,” (on the right) is unsolvable to me. Now, I don’t know whether I’m confused by the letters X, Y and Z normally being used for denoting axes in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, or whether I’m too much of a humanist to understand how the circuit board is supposed to work here, but with zero feedback from the game and several hours of cracking open the puzzle for the sake of a democratic write-up, no can do!

As the compo’s voting period is all but over, and the two games below warrant equal space, time and attention - and since many other players have reported similar troubles - we will have to leave the very tangible flaws of this puzzle for Stevens himself to solve (for instance, why does the circuit barely cover one fourth of the available screen, when more explanatory details could be shown?).

The tragedy of this all is that I have yet to see whether Stevens’ marketing of the game (“Do you love ACTION and SEX and MYSTERY?”1) as an adult-oriented experience has any bearing on the game’s subsequent content. Whether the game is smart, funny, crude or simply distasteful, I cannot know until I fix the damn ‘sputter. April is the cruellest month, huh?

To end, let me just briefly discuss what I think is to blame here, that is, beyond the aforementioned puzzle: Much like Limey Lizard, Hard Space has to be considered a descendant of Space Quest. As we all know, the series is both particular and persnickety - like The Many Deaths of Roger Wilco puts it, “finding all the ways of killing off Roger is half the fun of playing” - and overall, quite the exercise in masochism (or sadism, if you happen think like the website above) and foolhardy persistence.

In these terms, in an era where the rest of the adventure gaming scene is increasingly moving away from the Sierra style and towards the more forgiving structures of the LucasArts tradition and even into the casual (see Eternally Us, for instance), Stevens’ stubbornness has to be lauded - at the very least - for retaining versatility in the, uh, the space-game adventure gaming space.

Fin.

P.S.

I’ll let you know of any progress in the comments section. Do let me know if you got the puzzle.

Snakes of Avalon

Igor Hardy, perhaps better known for maintaining the excellent adventure developer hub A Hardy Developer’s Journal, has also produced an April game together with Alex van der Wijst. Their entry, Snakes of Avalon, concerns the decidedly psychedelic and hallucinatory story of Jack the barfly, who accidentally happens upon a devious murder pact. As he begins to uncover the dastardly plot, despite his obvious self-caused no-go condition, Jack holds a meeting with his conscience and proceeds to try and make a difference - even if only within the confines of his neighbourhood watering hole.

Only, nobody else around wants to lend an ear to the poor soul; zero faith is placed on Jack’s abilities, his perceived agency so diminished that the only thing seen to move him at all is booze. In these terms, Jack often seems defined by other people’s responses to him. Bob the barkeep, for instance, predicts but an early grave for Jack, mocking him of his addiction to cheap liquor; Mike, the compulsory chiselled local tough guy, has fun at the expense of Jack’s physical shape.

Only, nobody else around wants to lend an ear to the poor soul; zero faith is placed on Jack’s abilities, his perceived agency so diminished that the only thing seen to move him at all is booze. In these terms, Jack often seems defined by other people’s responses to him. Bob the barkeep, for instance, predicts but an early grave for Jack, mocking him of his addiction to cheap liquor; Mike, the compulsory chiselled local tough guy, has fun at the expense of Jack’s physical shape.

A major thread to the game is then how Jack constantly tries to prove his doubters wrong despite being already somewhere far beyond mere alcoholism. Hardy characterises the game the following way:

…consider the fact that there always happen to be snakes in rat-hole. In this particular case, Jack happens upon a particularly nasty conspiracy organized by a bunch of them. He takes an oath to give his best to stop them. Too bad then that he is a complete drunk, who has trouble discerning reality from hallucinations. And of course it all happens on Avalon - the ancient, mythical island.2

Avalon, the bar that functions as the setting of the game, feels like a spin-off of the legendary Lefty’s; both are decorated with the antique head of a moose, for instance, forming an intriguing lineage (see the screen captures on the left and below). Equal emphasis is placed on the presence of the bathroom, too.

Avalon, the bar that functions as the setting of the game, feels like a spin-off of the legendary Lefty’s; both are decorated with the antique head of a moose, for instance, forming an intriguing lineage (see the screen captures on the left and below). Equal emphasis is placed on the presence of the bathroom, too.

But not much else here is derivative. What the game truly excels at is the decidedly unique spin it puts on the competition’s spatial restriction: By utilizing a mid-screen division of high and low, the game offers an example of what we often call the “seedy underbelly.”

Equally important, in the context of the compo, is Jack’s refusal to leave the bar, a manifestation of his psychological dependence and addiction. In this way, better than any other game in the compo, Hardy and van der Wijst’s entry explores the one-room concept to its very limit.

Equally important, in the context of the compo, is Jack’s refusal to leave the bar, a manifestation of his psychological dependence and addiction. In this way, better than any other game in the compo, Hardy and van der Wijst’s entry explores the one-room concept to its very limit.

The titular hero, much like the aforementioned setting, is of the Lafferian archetype. In fact, the game’s graphics, while vastly more Paint-erly, are still reminiscent of the Leisure Suit Larry series, with especially the background art recalling the ever-so-slightly skewed structures of the latter-day Lowe-crafted Leisure Suits.

While the game’s looks hardly hold a candle to commercial ventures, they are nevertheless in no way detrimental to the overall experience. Indeed, a great deal of entrepreneurial diligence has been applied to the graphics: Nearly everything is animated, and the bar’s population is constantly changing and revolving, creating not only a fantastic sense of liveliness, but also of time passing.

While the game’s looks hardly hold a candle to commercial ventures, they are nevertheless in no way detrimental to the overall experience. Indeed, a great deal of entrepreneurial diligence has been applied to the graphics: Nearly everything is animated, and the bar’s population is constantly changing and revolving, creating not only a fantastic sense of liveliness, but also of time passing.

Much of the storyline is also augmented with semi-animated cutscenes, which a great deal of work must have gone into; for a MAGS entry the game indeed sports massive amounts of action and movement. Some interesting artistic touches, like the crazy train (on the right) exist; a selection of music, which I assume to be from the public domain, is not quite as successful in creating ambience, instead serving to confuse the temporal placement of the game.

Much of the storyline is also augmented with semi-animated cutscenes, which a great deal of work must have gone into; for a MAGS entry the game indeed sports massive amounts of action and movement. Some interesting artistic touches, like the crazy train (on the right) exist; a selection of music, which I assume to be from the public domain, is not quite as successful in creating ambience, instead serving to confuse the temporal placement of the game.

Curiously, the mouse buttons for look and use are inverted here compared to the usual paradigm, something that threw me off for a brief moment: Cognitive lock-in, I guess. As far as the puzzles go, once you get the gist of Jack’s internals, they become a smooth sailing, as the game constantly takes advantage, both in regards to its puzzles and its narrative, of its setting; only one or two inventory puzzles went decidedly beyond what could have seen to constitute Jack’s muddled-up inner life.

A thread of magic realism penetrates the internal logic of the game in a way that makes everything that happens to Jack still seem human-size and understandable. All in all, the game is a helter-skelter collage of events and occurrences that ultimately render its otherwise tragic protagonist a sympathetic - and quite a bit heroic - figure, even if only for a fleeting moment.

Two things of note: The game’s LucasArts metaphor is surely not lost on players! On that topic, do check out our story on goodwill and LucasArts. What the Arthurian Avalon has to do with all this I haven’t the faintest of clue, though.

Space Pool Alpha

Last but not least, Space Pool Alpha by Steve McCrea, Sheldon Moskowitz and Mark Lovegrove (against the rules, again?!) is a highly polished arcade experience that illustrates the inconceivable yet surprisingly potent combination of, yes, Asteroids and pool.

Let’s just… let’s stop and dwell on that for a moment: While the authors sell the game as an “intergalactic arcade sports simulation,” I don’t think that particular turn of phrase sufficiently illustrates all the different layers of the game.

What Space Pool Alpha is, really, is a video game whose mechanics are loosely based on the real-life ™ game family of cue sports, games played on a specifically designed table and with cue sticks and pool balls. This real-world game and its varying rule sets have been abstracted and subsequently brought into the computerized realm, as a symbol-based simulation, with another such abstraction - the science fiction of a space shuttle stuck in an asteroid belt, shooting its way out - layered on top of it.

This mixture of simulation-upon-simulation is then transformed together, by Mr. McCrea and co., into something entirely different. On top of everything, all this has been conceived and executed – successfully, if I may add – on an adventure game development system! Goodness, there are so many facets to this erratic entry that I simply cannot fathom how our brains cope with it all.

This mixture of simulation-upon-simulation is then transformed together, by Mr. McCrea and co., into something entirely different. On top of everything, all this has been conceived and executed – successfully, if I may add – on an adventure game development system! Goodness, there are so many facets to this erratic entry that I simply cannot fathom how our brains cope with it all.

But I have played Space Pool Alpha and survived. In fact, it all could not be simpler as you are playing the game. The whole concept only becomes a brain-buster when you start thinking about it.

(Sorry.)

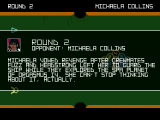

The graphics, then, pay successful homage to the original wireframe-based Asteroids style, retaining these ultra-familiar translucent shapes down to a tee. The sound effects similarly enhance the fiction, of a retro game, very successfully.  The enemies, in arcade fashion, all have colourful portraits and background stories that tell players more about their opponents’ temperaments. The bots are largely competent and the gameplay is a polished experience, with no apparent issues sans some advantageous shooting methods. All in all, there are four modes of play: A quick tutorial and separate modes for practice, tournament and 2P each.

The enemies, in arcade fashion, all have colourful portraits and background stories that tell players more about their opponents’ temperaments. The bots are largely competent and the gameplay is a polished experience, with no apparent issues sans some advantageous shooting methods. All in all, there are four modes of play: A quick tutorial and separate modes for practice, tournament and 2P each.

While I did find Lovegrove’s midi stylings to be somewhat more jarring here than usual, the problem has much to do with my idea of pool being better suited to a loungier, jazzier style.

That’s all from me, folks - and what a task it was! So many interesting entries this month. Again, the entries can be voted for up until the 17th of May, so you still have some time to familiarize yourself with the rest of the entries. Also, many of the games mentioned in part I, part II and here have also seen further revisions and updates since their original release. You can find more about these improvements by checking out the corresponding threads in the Completed Game Announcements section of the AGS forums.

Finally, also remember that we have quite a bit of existing Adventure Game Studio coverage on the website - feel free to take a look. Questions? Comments? Have a go below!

What a great sum up of all the games! Well done. By the way, the solution to the transputter can be found here: http://gamesolutions.efzeven.nl/hard-space-walkthrough-progzmax2010/

Thanks a lot for the tip Leon! I happen to be incredibly stubborn when it comes to adventure games (in more than one way), so A) I am definitely yet to give up on Hard Space and B) I’ll try and work out the solution without a walkthrough for a while longer still!

Good to know one exists, in any case.

Hey, some great thoughts on Snakes of Avalon in here. You came up with connections I did never really think of, like the one to Lefty’s bar from Larry 1, which is very flattering for our game.

Now, I only played the EGA version of Larry and I doubt after all this time a 5-pixels moose head would resurface as an idea in my head. Consequently, I think the similar trophy in Avalon is just based on the same bar cliche (a cliche we were very happy to exploit and animate ;) ). The major difference between the bars is that Lefty’s establishment puts more emphasis on “sleazy” and “tacky” as styles in interior decorating, while Avalon is cheap in the literal “dirt on walls, bug-infested and rotting” sense.

That said, I must confess I love visiting all sorts of taverns and inns as locations in games I play. Places like Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, or those which the hero of Quest of Glory series visits, where new crazy, quests are formed from conversations with strange, often mysterious patrons, are my kinds of places. :)

And in response to “what the Arthurian Avalon has to do with all this”, I admit that not that much - Avalon is just a good name for a bar… Nevertheless, the mythical status of Avalon’s name strengthens the “thread of magic realism” you mention. Also, a magical island without any clear location, and easy means of getting onto is a perfect illustration of how the bar location is isolated from the rest of the world (at least in Jack’s mind) and works well with the “outside of any specific time” feel that the combination of old jazz tunes with more modern world elements gives. And lastly, I’m a big fan of Mamoru Oshii’s Avalon. :)

Finally, too bad you didn’t write more about Alex van der Wijst. He is a veteran game maker who created great titles like The Winter Rose, Charlie Foxtrot and Besieged. These are lengthy and complex games, and some of best AGS offerings ever, easily beating in quality the current crop of indie adventure games. It was a blast working together with him on Snakes.

Most excellent, Hardy - trading and sharing insight was one of the top reasons I published these posts in the first place. Your comment regarding Alex’ contributions is similarly on point; I’ve included a link to his personal website now.

While I’m not intimately familiar with his catalogue of games, I can at the very least vouch for Besieged!

Sounds like you need to download the Full Release of Hard Space based on those screenshots, Martin:

http://www.bigbluecup.com/yabb/index.php?topic=40883.0

Also, just to set a few things straight:

I hated Space Quest and its need to frustrate the player, so that has never been my intention with any of my games. Oddly enough, most people have told me that Limey Lizard was my easiest game, so I’m not sure how seriously to take your comparison of it to Space Quest. The Transputter puzzle was solved by both my testers without any feedback from me so I figured it was good to go, though I have added some more hints in the dialog and changed up a few things to make it easier on lower difficulties. I do applaud you for not wanting to resort to a walkthrough, though; to me that ruins the entire point behind playing an adventure game in the first place. Thanks for the article, and feel free to drop me an email if you need some hints or something with Hard Space.

-Shane

Oh and good catch on the ship designation gaffe :). That was one of those things I kept meaning to fix and kept forgetting to.

ProgZmax, thanks for your response! First things first, yes, I did use the very first release for each game to keep the playing field level. The download link provided in the thread you mentioned was not working at the time of writing, but I’ll drop back in later.

Obviously we had a debate regarding the inherently dubious quality of publishing a discussion of game not yet played through - in normal circumstances, we obviously don’t do this - but here, I thought my inability to proceed contributed some unique flavour to the article. Hopefully this in part justifies my decision alongside the obvious need to have the article published before the end of the competition.

I have no idea how long I will be able to stick to my guns and stay away from using walkthroughs, but so far we have only had to pay heed to to deadlines that make sense internally.

As far as the Space Quest reference (which I tried to supplement with a mention of the Star Trek adventures), I didn’t have the time and, uh, space to explain my own feelings towards the Space Quest series more closely. Like I mentioned earlier, I’m very stubborn indeed, and I didn’t mean to use the Space Quest reference as negatively as it may have come off to someone that doesn’t enjoy the series: I’ve completed each of the games in the past, and while they are punishing indeed, there are obvious merits to them too, one being the magnificent rush that you get from cracking a puzzle that you thought impossible.

My favourites two parts in the series would have to be numbers four and five. How about you guys?

[…] deliver our Snakes to keep you warm for the remainder of the holiday season. The game hasn’t been compared to Leisure Suit Larry for nothing after all. This entry was posted in Just Info. Bookmark the permalink. ← UPDATE […]

[…] deliver our Snakes to keep you warm for the remainder of the holiday season. The game hasn’t been compared to Leisure Suit Larry for nothing after […]